The Hastings Net Shops

Steve Peak

Row P in the 1920s.

Row P in the 1920s.

Row Q in the 1920s.

Row Q in the 1920s.

The Hastings net shops are unique - tall, thin wooden sheds, up to three stories high, painted black, standing in neat rows on a part of beach near the sea. Sheds of various shapes and sizes types have stood on this shingle in front of Hastings Old Town for many centuries, but it was a town planning decision in 1835 that created the striking architectural design and layout that can still be seen today.

The exceptional features of the Hastings net shops resulted in 39 of them in 2010 being designated by English Heritage as being Grade II* (grade two star) ‘listed buildings’ - national heritage assets, at the second highest level.

The shops are the traditional storage buildings of the Hastings fishing fleet. They were used in the past to stow gear made from natural materials - cotton nets, hemp ropes, canvas sails etc - which would rot if left in the open, especially when wet. If possible, the items would be dried on the beach first, and then kept dry inside these weather-proof stores.

Row U about 1895.For many centuries before 1835 there were wooden sheds of varied shapes and sizes on the Old Town beach (also often then called the Stade, or the Stone Beach). This beach was liable to be flooded by severe gales which could damage or destroy the sheds, so they had to be easily rebuilt. Most were standing on stones or stumps of wood which let the sea run under them. Some were on wheels, while other sheds were simply old boats turned upside down, or stood upright on their stern.

Row U about 1895.For many centuries before 1835 there were wooden sheds of varied shapes and sizes on the Old Town beach (also often then called the Stade, or the Stone Beach). This beach was liable to be flooded by severe gales which could damage or destroy the sheds, so they had to be easily rebuilt. Most were standing on stones or stumps of wood which let the sea run under them. Some were on wheels, while other sheds were simply old boats turned upside down, or stood upright on their stern.

Nets and ropes were the two main pieces of gear that were stowed in the sheds, so until well into the 19th century the buildings could be called either a ‘net shop’ or a ‘rope shop’. They were known as ‘shops’, not because they were selling something, but because that is an old term for a working place, as in ‘workshop’. In recent years it has been mistakenly thought the net shops were also known as ‘deezes’, but this was then the name for a place where herrings were dried. Deezes were mistaken for net shops because they were similar-looking small wooden buildings. There were many deezes on and near the Stade up until World War One, but then the international herring market collapsed and the number of deezes was greatly reduced.

From the late 18th century Hastings became an increasingly popular seaside resort. This started a steady development of shops, inns and lodging houses on the Old Town’s seafront, gradually eating into the limited amount of beach that was available for the fishermen to use for their boats and sheds. Hastings Corporation at first had a relaxed attitude to the siting of the net and rope shops, allowing them to be in several different places, as long as they were not fixed to the ground, so that they could be easily moved at the corporation’s request or instruction.

Looking east from the Cutter pub in 1823. On the left is the Lower Lighthouse.

Looking east from the Cutter pub in 1823. On the left is the Lower Lighthouse.

But the boom in the tourist trade in Hastings from c1815 turned the location of the net shops into a serious problem in the early 1820s. There were then about 60 net shops between Tamarisk Steps (next to the Dolphin pub) and the Cutter Inn, and space was becoming more limited as the town grew. In addition, several large net shops had been let for other trading purposes as the ground became more valuable. This growing problem reached a climax in May 1824 when there was a near-riot as Hastings Corporation tried to move some net shops and fishmarket stalls standing between the bottom of the High Street and the Cutter Inn in order to widen the sea-front road. Seven fishermen and fish sellers ended up in court after they physically stopped corporation officers from moving their property.

The fish-selling stalls, sheds and net shops at the bottom of the High Street in the 1850s. Below is the 1833 plan, with the High Street in the middle. Many horse capstans are drawn, far more than were on the ground.

The fish-selling stalls, sheds and net shops at the bottom of the High Street in the 1850s. Below is the 1833 plan, with the High Street in the middle. Many horse capstans are drawn, far more than were on the ground.

This resulted in the corporation trying to take a tougher stand on the layout of the Stade. But another legal row took place in 1833 over the increasing use of what should have been net shops for other commercial purposes. The indecisive result of this case led Hastings Corporation to commission the drawing of plans which showed exactly where all buildings were on the Stade.

The eastern 1833 plan, from the Bourne Stream to the East Well, has been lost, but the plan covering the area west of the stream have survived. They show that there were then several groups of net shops and similar buildings standing on East Beach Street and East Parade, ie, on what is now the A259 west of its junction with Rock-a-Nore Road. The most westerly group was two adjoining rows of 10 net shop-type buildings, standing opposite the Lower Lighthouse (which still exists, next to the west end of the restaurant). Opposite the London Trader pub there were two more adjoining rows, with seven net shops in all. A hundred yards west of these was an assorted collection of wooden buildings, some probably net shops, while 100 yards to the east of the seven (at today’s A259 junction) was a near-straight line of sheds, five of which were probably net shops.

The 1833 plan also shows (on the right) that next to the London Trader was a linked row of 10 net shops, running east-west. Eight of these are still standing, as cafes and small shops, and they are the only known surviving net shops which definitely date from before 1835. Some of the eight wooden net shop-type buildings that stood on the landward side of East Parade and East Beach Street in the 1833 plan may have been incorporated into the buildings which stand there today, but all the ones on the seaward side of the road have gone, having been cleared by Hastings Council.

Building the Net Shops

At least 36 of the 39 net shops listed as grade II* in 2010 were built from 1835 onwards. This was a result of the construction in 1834 of the first Hastings sea-defence groyne, beneath the cliffs at Rock-a-Nore. The groyne was designed to protect the Old Town from a growing number of invasions by the sea, caused by the construction of groynes in front of the new town of St Leonards to the west, which was affecting the longshore drift movement of shingle (west-to-east). The first Hastings groyne was laid out at near right-angles to the cliff in what is now Rock-a-Nore Road, a few yards/metres to the east of where the Shipwreck Museum is today.

Until then there was no road, just a rough track along the beach at the bottom of the cliff, with the sea almost coming up to it. The view westward from Rock-a-Nore in 1823.

The view westward from Rock-a-Nore in 1823.

A large amount of shingle quickly piled up on the west side of that first groyne (made of timber), creating new ‘ground’ in front of the cliffs. The number of fishing boats was then increasing steadily and the existing beach was too small to hold the boats and their net shops, so boat owners quickly moved onto this new piece of land, from Tamarisk Steps eastwards. Hastings Council, however, immediately claimed ownership of that ground, and cleared and levelled it. Remembering the riot of 1824 over the siting of some net shops, and the 1833 legal row about what they could be used for, the corporation tried to make sure there would be no similar problems in future by making the fishermen sign a ‘memorandum of agreement’. This gave their net shop a specified piece of ground for fisheries purposes only, and for which they would pay an annual rent for it. But until recent years many fishermen disputed the Council’s ownership claim, with some refusing to pay the ground rent.

In August 1835 the Council signed its first 12 memoranda for this new piece of beach. As most net and rope shops had until then been about eight feet (2.45 metres) square, these first agreements let the fishermen hire a piece of ground “measuring eight feet square ... whereon a rope or net shop for the use of the fishery is intended to be placed”. Some later agreements gave larger sites, up to about ten feet (3 metres) square.

Row V next to the Fishermen’s Church in the 1890s. Several oilskin smocks are drying in the sun. There are three horse capstans for hauling boats out of the water. On the right are two beach anchors for helping stop boats sliding down the beach as they were being launched.

Row V next to the Fishermen’s Church in the 1890s. Several oilskin smocks are drying in the sun. There are three horse capstans for hauling boats out of the water. On the right are two beach anchors for helping stop boats sliding down the beach as they were being launched.

The annual ground rent was two shillings (10p today), rising in 1846 to five shillings (25p today) – which it still is now! Every year Hastings Council sends each net shop owner a 25p invoice for the shop’s site, with the town’s net shop logo in the top-left corner. The cost of preparing the invoice, printing it, paying its postage, handling the income payment and maintaining the appropriate file is somewhat more than 25p per year.

Back in 1835 it was clear that the shops had to be lined up in double rows with large gaps between them so that boats could be hauled up close to the cliff, as the sea was still coming close inshore. Horse-turned capstans were set up between the rows. The limited ground space of all the net shops meant that they could not expand outwards, and they could only get bigger by becoming taller, forcing them to become slim lofty buildings, as happened with the skyscrapers in New York.

Hastings Council gave each row of net shops an identifying letter, and each net shop itself had its own number, with number one being closest to the road. Net shop U3, for example, is in row U and was originally the third one away from the road, although numbers one and two have now gone. The rows were lettered from west to east, with rows A and B being the group opposite the Lower Lighthouse in East Parade in the 1833 plan, and Row W being behind what is now the Fishermen’s Museum. Rows M-W were all built from 1835 onwards.

Maps of 1956 (above) and 2017 (below) showing the layout of the net shops. Each row had a letter as its title, and every net shop had a number. As an example, the Net Shops Museum is U3 – number 3 in Row U. They have been coloured in the maps to make them easier to see.

Maps of 1956 (above) and 2017 (below) showing the layout of the net shops. Each row had a letter as its title, and every net shop had a number. As an example, the Net Shops Museum is U3 – number 3 in Row U. They have been coloured in the maps to make them easier to see.

Today the most westerly surviving row is part of L, being the three net shops opposite Winkle Island. The three net shops here may possibly have been built shortly before 1835, as part of Mercers Bank, although it is more likely that they were built after the 1846 fire (see below).

The rows were roughly equally spaced, except for the much larger gap between Rows L and M. This provided an emergency area for boats to be hauled onto during severe storms when the sea came a long way up the beach. Today the Hastings Contemporary art gallery stands on a substantial part of it.

All the post-1835 net shops were built to a roughly similar design: a very slim frame, with diagonal bracing to give strength against the wind, and overlapping planks on the outside. Headroom on each floor was low, making it easier for fishermen to lift up and hang heavy nets on the beams supporting the floor above. In each ceiling there was an opening, about two feet square, with a ladder attached to the wall going up through it. Each floor had its own door through which gear could be brought in, and opening outwards so that the maximum amount could be stored inside. Some net shops had small shuttered windows.

Horses turning two capstans to haul boats out of the water, in front of Row S in the early 1900s.

Horses turning two capstans to haul boats out of the water, in front of Row S in the early 1900s.

The outside of the net shops was always boarded, and they used to be covered in tar, as were the boats. This was readily available at a cheap price from the Hastings Gasworks, which was started in 1830. Tar was a by-product of making gas from coal. After the gasworks closure in 1969, however, tar became increasingly hard to obtain, and since the 1980s a black paint called ‘black tar varnish’ has been used.

The original thick tar was almost hard, and had to be melted in hot water and then slapped on in semi-liquid form. This gave the net shops an attractive encrusted appearance, which can still be seen on a few of them (eg, the north side of U3), and on the 1912-built Hastings lugger Enterprise RX 278 inside the Fishermen’s Museum.

The original thick tar was almost hard, and had to be melted in hot water and then slapped on in semi-liquid form. This gave the net shops an attractive encrusted appearance, which can still be seen on a few of them (eg, the north side of U3), and on the 1912-built Hastings lugger Enterprise RX 278 inside the Fishermen’s Museum.

Sadly the tar made the buildings very combustible, and many net shops were lost to fires. The biggest fire, in 1846, burnt down about 20 net shops on, and to seaward of, today’s Winkle Island. A public subscription to help the owners of these lost net shops covered their rebuilding costs, including probably those that form today’s Row L. The donations also had enough surplus to build the East Well (below), the fresh water supply still standing next to the East Hill Lift. Fresh water was a commodity hard to find in Hastings Old Town in the early Victorian years, and the East Well was a valuable resource for fishermen and their families.

The East Well in the 1890s.Until the early 19th century the net shops had been relatively small, compared with those surviving today, because fish were more abundant in the sea, and therefore less net was needed to catch them. But the creation of the railway network across Britain in the 1840s and 50s turned many previously small ports - such as Hull and Grimsby - into major landing places. This greatly increased the availability of fish nationally, creating a large-scale market, and therefore meaning more money could be made by bigger boats. By the 1840s many Hastings boat owners had had big, 50-feet long fishing vessels built to work the south and east coasts of Britain, from Lands End to Cape Wrath, landing to the new rail-linked markets that were appearing.

The East Well in the 1890s.Until the early 19th century the net shops had been relatively small, compared with those surviving today, because fish were more abundant in the sea, and therefore less net was needed to catch them. But the creation of the railway network across Britain in the 1840s and 50s turned many previously small ports - such as Hull and Grimsby - into major landing places. This greatly increased the availability of fish nationally, creating a large-scale market, and therefore meaning more money could be made by bigger boats. By the 1840s many Hastings boat owners had had big, 50-feet long fishing vessels built to work the south and east coasts of Britain, from Lands End to Cape Wrath, landing to the new rail-linked markets that were appearing.

These large three-masted luggers (sailing vessels using the lug rig) carried more fishing gear, and therefore needed big net shops. However, the 50-footers gradually fell out of use during the 1870s when the new major ports had their own even bigger vessels built, which could not be based in Hastings because they were of a different design and there was not room for them on the Stade. But at the same time the Hastings market for fish was growing, and supplies for this could be caught in the eastern English Channel by smaller, 30-feet long luggers. By the late 1860s there were so many fishing boats at Hastings - both large and small - that there were about 120 net shops, of many shapes and sizes.

The Stade in the early 1870s. The three boats nearest the camera are laid-up big luggers. At low tide ,a collier is unloading coal into horse-drawn carts. The white oblongs on the beach are washing being dried in the sun. Centre-right is Mercers Bank, and in the foreground is Row M of the net shops. In the distance is Hastings Pier, which opened in 1872.

The Stade in the early 1870s. The three boats nearest the camera are laid-up big luggers. At low tide ,a collier is unloading coal into horse-drawn carts. The white oblongs on the beach are washing being dried in the sun. Centre-right is Mercers Bank, and in the foreground is Row M of the net shops. In the distance is Hastings Pier, which opened in 1872.

From the mid-19th century until World War One the biggest catches of fish at Hastings were mackerel and herring. Both were caught using drift nets, but different types of nets had to be used because the two species were not the same size and therefore needed nets with different meshes. Mackerel were caught in the summer and herring in the autumn and early winter, so in those seasons the unused nets - up to a hundred in number - had to be stored dry in net shops. The nets would be coiled up, tied across the middle and then hung from hooks on the ceiling beams, with mackerel nets on one floor and herring on another. Trawling gear would usually be kept on the ground floor, and in the cellar if there was one.

The Decline and Fall

From the 1840s Hastings Old Town expanded along under the East Hill, with many industrial and commercial businesses being set up along the foot of the cliff. To make room for these buildings and their traffic several net shops were moved from the inland end of their row to the seaward end. In 1859 the track was given the official name of Rock-a-Nore Road.

In the early 1850s Hastings Council also gradually began clearing the net shops on the seaward side of East Parade and East Beach Street. Rows A and B were probably removed completely in 1859.

One of the severe storms in the early 1880s that destroyed many net shops.

One of the severe storms in the early 1880s that destroyed many net shops.

In November 1875 a storm washed away 14 net shops, and in the early 1880s a large number were destroyed in severe gales, including the whole block opposite the London Trader pub. This damage to the net shops and other seafront buildings was the result of Hastings Council refusing to build new groynes in front of the Old Town, hoping the sea would literally wash the fishing industry off the Stade, forcing the fleet to move to Rye. The Council would then have built the needed groynes and created tourist attractions on the new beach that would appear. But this policy created such a public outcry that the Council had to back off from this anti-fishing industry strategy, and instead to build a large new groyne at Rock-a-Nore, which was completed in 1887. Number Three groyne, as it is officially called, made the beach much bigger to the south, thereby stopping the sea from threatening the net shops, and removing the main reason for them having rocks, stumps or wheels underneath them.

From the 1890s the Hastings fishing industry began a long period of decline that was to last until the end of World War Two. As the fleet shrank, and the town’s tourist industry grew, Hastings Council steadily took over parts of the Stade for use as car parks, amusement centres, coach parks and other trades. The last major loss of net shops took place in 1929, when the large mixture of old buildings forming Mercers Bank (on, and to seaward of, today’s Winkle Island) were nearly all removed so that Rock-a-Nore Road could be widened to what is now. There were about 13 net shops in Mercers Bank, and all bar three of these were removed, along with all the other buildings. The only survivors of Mercers Bank are the three net shops forming Row L.

When the fishing industry revived after World War Two, the remaining net shops began to be used less, because from the 1950s most of the natural materials used in fishing gear were being replaced by nylon and other weather-resistant synthetic substances that did not need to be kept dry, and therefore did not have to be stored inside buildings. The fishermen were also constructing their own sheds out on the beach, primarily to house a winch to haul their boat out of the sea, but also to store gear.

By the mid-1950s it had become clear that the net shops were a tourist attraction, while at the same time their future was in doubt because they were being much less used by the fishermen. How were they to be looked after? From 1956 the Old Hastings Preservation Society (OHPS) took the initiative. The OHPS had been formed in 1952 to defend the historical heritage of the borough, and in 1956 had created the Fishermen’s Museum in the former church in Rock-a-Nore Road. For many years donations collected in the Museum were used to help pay for repairs to the net shops.

In early 1959 the OHPS paid for three net shops to be re-sited so that pavement could be laid along the seaward side of Rock-a-Nore Road.

The second biggest fire amongst the net shops, after that of 1846, took place on 24 June 1961, destroying four at the seaward end of Rows T and U, and damaging net shop U3. This spectacular blaze actually helped the surviving net shops, for it highlighted their deteriorating condition and prompted more public help. A restoration fund was set up, and it received enough donations to pay for four new three-storey net shops to be put up on the same sites. They were built in sections in Hastings Council workshops and erected on new concrete bases.

In November 1969 a fierce gale blew down the old net shop standing next to the Fishermen’s Museum which had been used for exhibition purposes. The Museum and the OHPS had a new three-storey replacement built, which still stands there today, displaying many fisheries artefacts.

Restoration

Row M in the early 1950s. On the cliff are two wartime gun emplacements: one, just to the right of where the roofless net shop’s roof should be; the other, on top of the cliff above the sixth net shop from the left.

Row M in the early 1950s. On the cliff are two wartime gun emplacements: one, just to the right of where the roofless net shop’s roof should be; the other, on top of the cliff above the sixth net shop from the left.

By the late 1970s many of the net shops were in an advanced state of structural disrepair and much investment was needed in order to preserve them all. Spurred on by the OHPS, Hastings Council in 1980 carried out a survey of all the net shops. Then in 1984 local architect Ralph Wood, vice-chairman of the OHPS, announced that the society and Hastings Council had set up a working arrangement, whereby they would both raise funds for the restoration work, at no expense to the fishermen, and the OHPS would administer the work as it was carried out. The Council gave £1,500 pa for three years to pay for materials, and OHPS plus English Heritage met the labour costs.

Row T standing on legs after the war.In late 1985 I (Steve Peak) became a trustee of the OHPS, and joined Ralph in running his new scheme. This was a few months after the publication of my book Fishermen of Hastings, which helped persuade Hastings Council to adopt a more positive approach to supporting the fishing industry and in preserving the maritime heritage on the Stade (including the net shops). I was also then using net shop U3 as a store in my maintenance of the 1919 Hastings fishing boat Edward and Mary RX 74, which in 1983 I had saved from being broken up, and had placed on the beach between net shop Rows U and V (and it is still there today).

Row T standing on legs after the war.In late 1985 I (Steve Peak) became a trustee of the OHPS, and joined Ralph in running his new scheme. This was a few months after the publication of my book Fishermen of Hastings, which helped persuade Hastings Council to adopt a more positive approach to supporting the fishing industry and in preserving the maritime heritage on the Stade (including the net shops). I was also then using net shop U3 as a store in my maintenance of the 1919 Hastings fishing boat Edward and Mary RX 74, which in 1983 I had saved from being broken up, and had placed on the beach between net shop Rows U and V (and it is still there today).

During the second half of the 1980s, Ralph Wood, myself and Hastings Council conservation officer Jim Corrigan together oversaw the rescue of many near-collapsing net shops, and obtained initial funding from English Heritage to start an annual schedule of both structural repairs and external maintenance.

Hastings Council is still carrying out an annual programme of looking after the net shops.

In 1988 two new three-storey net shops were built on vacant sites in Rows R and S; they are numbers R4 and S2. In 1993 the demolition of Hastings Fishmarket, built 1956, and the construction of a new larger one meant that a net shop at the seaward end of Row S had to be carried by crane to Row O; today it is number O3.

Upgrading

All the existing net shops on the south side of Rock-a-Nore Road were listed as Grade II buildings in 1976, and then upgraded to Grade II* in June 2010. English Heritage said at that time that: “The Net and Tackle Stores (Net Shops) on Rock-a-Nore Road in Hastings are listed Grade II*, for the following principal reasons:

"Architectural interest: they continue traditional building techniques, design and materials and each net shop individually reflects in its design, the specific function it was intended to fulfil;

- Historic significance: the net shops are invested with more than special historic interest as the physical evidence of the once thriving British fishing industry, from the C19 or before;

- Rarity: relatively few examples of these structures survive nationally and their small footprint, uniformity, three-storey nature, arrangement into rows; the large number that have survived, and the distinct circumstances that brought about these attributes, make the Hastings examples of more than special interest.

- Group Value: these net shops form a group with other listed net shops, including: 8-16 East Beach Street and Fishing Net and Tackle Store (immediately west of the Net Shop Jellied Eel Bar), Rock-a-Nore Road."

All bar one of these 39 buildings with the Grade II* listing are two storeys or more high. Also on this southern side of Rock-a-Nore Road are five other buildings which look like net shops but have not been listed; three (next to the fishmarket) do not have wood structures, being concrete block-built and timber-clad, and the others are the two halves of the fishing boat Golden Sovereign RX 40, standing upright.

Separate from these net shops on the south side of Rock-a-Nore Road are the ten buildings north of the road which were once net shops and were therefore listed as Grade II in 1976, but have not been upgraded; they are described in ‘Group Value’ by English Heritage, above.

The ‘Store’ is the Willis family net shop (far left, in 1920s) standing between the jellied eel bar and the Mermaid Cafe in Rock-a-Nore Road, which is seen in many old photographs. The other nine are the survivors of the ten that stood in the east-west line in East Beach Street next to the London Trader pub in the 1833 plan. All nine were converted into shops and cafes many years ago, but ironically these are the oldest known net shops, almost certainly being older than all the 39 that have been listed as Grade II*. It is possible that the Willis net shop is also pre-1835, but its age is unknown.

Net Shops Museum

Net shop U3 is the Net Shops Museum - the only museum of net shops in the world! It is one of the 12 net shops given the first ground leases by Hastings Corporation in 1835, and was probably built in 1835/36. Number U3 has three floors, plus a cellar. It originally had only two floors, but in the early 1900s the building was lifted up and another floor inserted underneath, along with the concrete-lined cellar. The roof and some of the top floor burnt off in the June 1961 fire which destroyed the four net shops on the seaward side (those standing there today have all been built since 1961).

The Net Shops Museum is centre-right here, and on the right in the next two pictures.

The Net Shops Museum is centre-right here, and on the right in the next two pictures.

Many of the items inside the museum are very old, going back well before World War Two. Some come from the sailing lugger EVG RX 152, which used this net shop until being blown up by a mine in Rye Bay in 1943. The owner of the boat and the net shop, Will ‘Ickle’ Curtis, then retired from fishing and gave the net shop to his son Jim, who, just before he died, in turn passed it on to me (Steve Peak) in 1988.

With Jim’s help, I had been using U3 as a store and workshop for the 1919 Hastings fishing boat Edward and Mary RX 74, which I had saved from scrapping and had placed on the beach in front of U3 in 1983. At that time much of the beach alongside Rock-a-Nore Road was hard ground covered in weeds, with most of the surrounding net shops in a poor state of repair. But the presence of the Edward and Mary prompted Hastings councillors and their officers into turning the space between net shop Rows U and V into a maritime heritage area, which it still is today.

During the 1980s I collected old fishing items that were being discarded because they were no longer needed, and many fishermen gave me interesting redundant objects. By the late 1980s U3 had become an ‘unofficial’ museum. After Jim died I decided to call it the Net Shops Museum, and I have maintained it ever since, keeping it as it was in the 1980s. In 1995 I became the honorary curator of the Fishermen’s Museum, and in the following years I gave that museum hundreds of the artefacts I had saved. I have also donated the Edward and Mary and the Net Shops Museum to the Fishermen’s Museum.

U3: above, in the 1920s, on the right

U3: above, in the 1920s, on the right

A striking feature of the Net Shops Museum is that it is leaning over towards the cliffs. This is because the bottoms of the two corner posts nearest the cliffs rotted many years ago, while the bottoms of the other two corner posts did not. As these four posts are the basis of the building’s structure, the whole net shop started tilting as the two posts near the cliffs rotted and sank into the shingle.

U3: in 2022

U3: in 2022

Around 1990, conservation officers who were helping restore the net shop decided they liked it listing – so they built a special structure inside the museum to keep it leaning over permanently!

Pictures

1854: On the left is the East Well, one of the few sources of clean water in the Old Town. On the right Is the timber store of the boat-owning Kent family. The four men are resting on a horse capstan.

1854: On the left is the East Well, one of the few sources of clean water in the Old Town. On the right Is the timber store of the boat-owning Kent family. The four men are resting on a horse capstan.

Late 1850s: Mercers Bank is on the right. The big roof in the background is today’s Royal Standard pub; all the other buildings in the picture no longer exist.

Late 1850s: Mercers Bank is on the right. The big roof in the background is today’s Royal Standard pub; all the other buildings in the picture no longer exist.

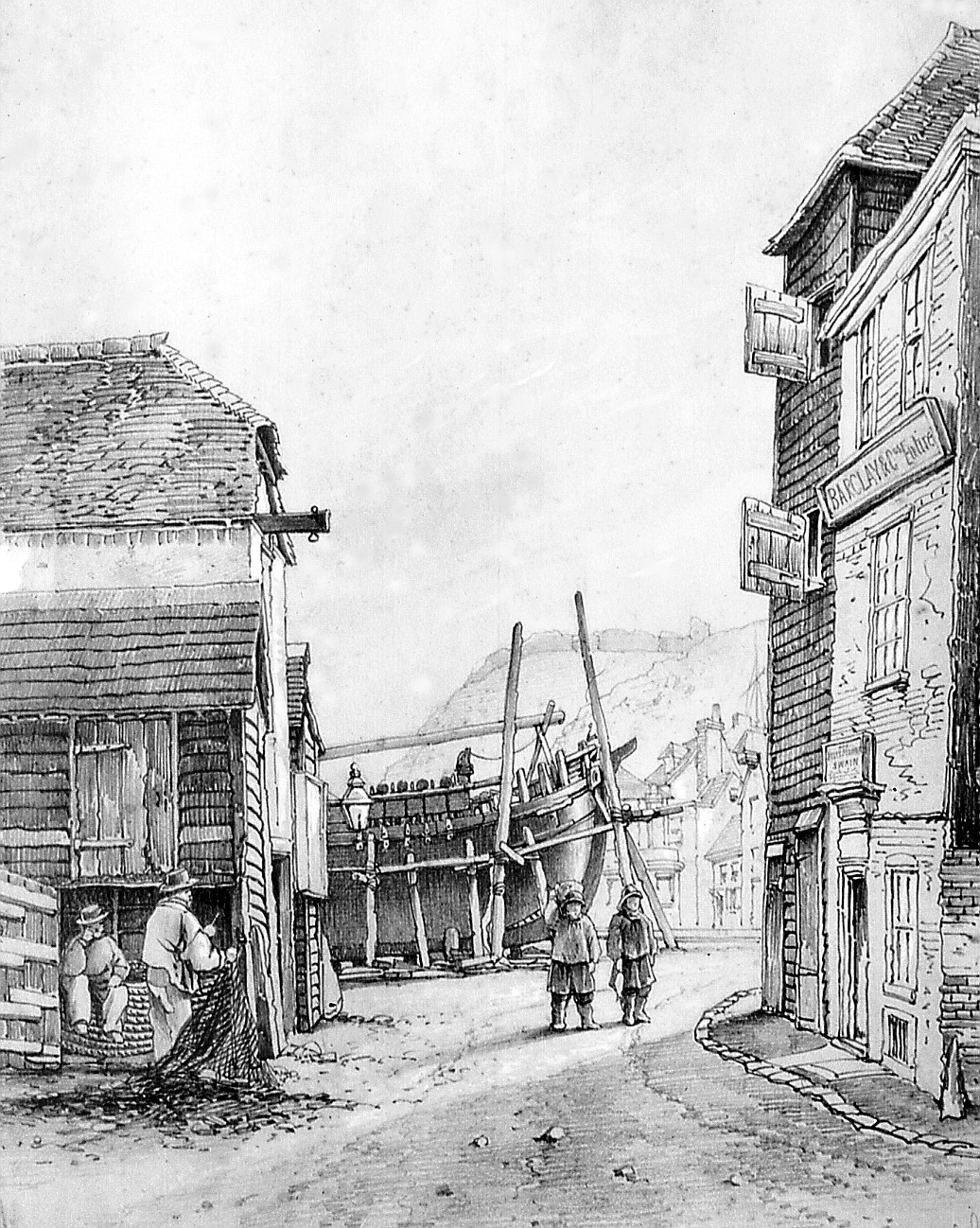

A picture by William Harriott which says at the bottom “Fish Market, Hastings. 2 Oct 1824”. Looking west from the bottom of the High Street.

A picture by William Harriott which says at the bottom “Fish Market, Hastings. 2 Oct 1824”. Looking west from the bottom of the High Street. 1852: A Hastings Council map. Pink buildings are made of stone or brick, the grey ones of wood. Centre-right is Mercers Bank. The Royal Standard pub is at the east end of East Street.The ten net shops in front of it are next to the London Trader pub.

1852: A Hastings Council map. Pink buildings are made of stone or brick, the grey ones of wood. Centre-right is Mercers Bank. The Royal Standard pub is at the east end of East Street.The ten net shops in front of it are next to the London Trader pub.

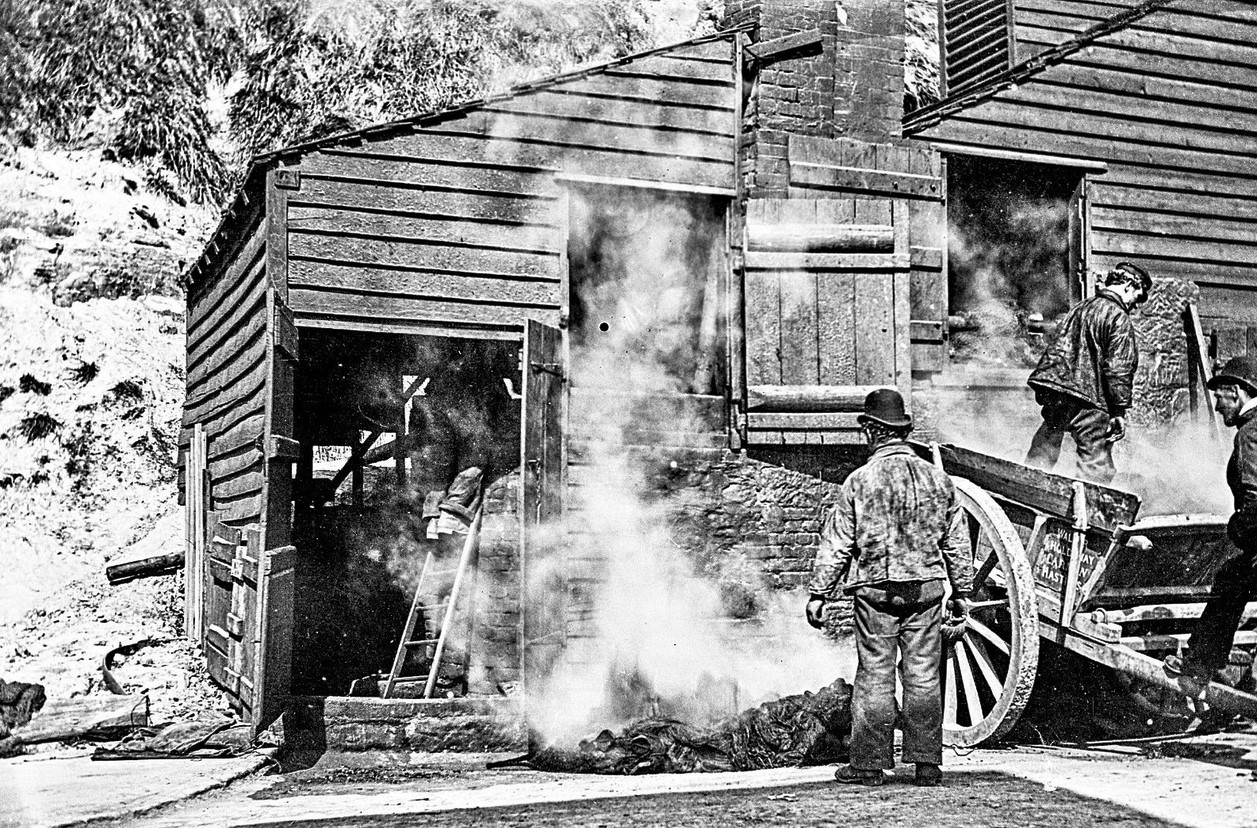

The tan house in Rock-a-Nore Road, now the café next to the East hill lift, in the late 19th century. Here fishermen tanned their nets and other gear to preserve them.

The tan house in Rock-a-Nore Road, now the café next to the East hill lift, in the late 19th century. Here fishermen tanned their nets and other gear to preserve them.

The early 1890s. It is flat calm, with no wind, so the engine-less fishing boats are all hauled-up on the beach.

The early 1890s. It is flat calm, with no wind, so the engine-less fishing boats are all hauled-up on the beach.

All aboard! On the beach in the early 1900s.

All aboard! On the beach in the early 1900s.

A horse turning a capstan to haul a boat up the beach, in 1936.

A horse turning a capstan to haul a boat up the beach, in 1936.

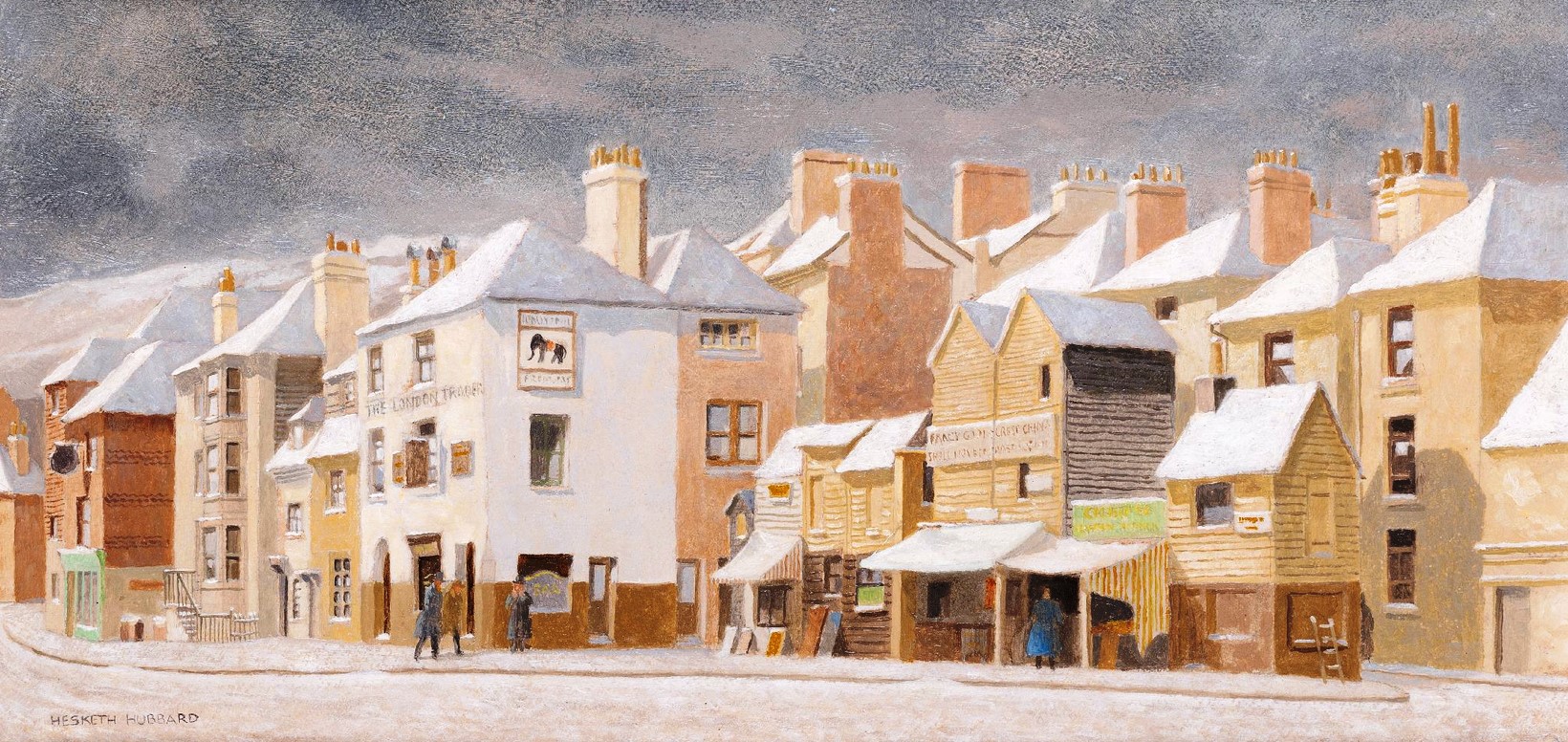

The London Trader row. By Eric Hesketh Hubbard 1892-1957.

The London Trader row. By Eric Hesketh Hubbard 1892-1957.

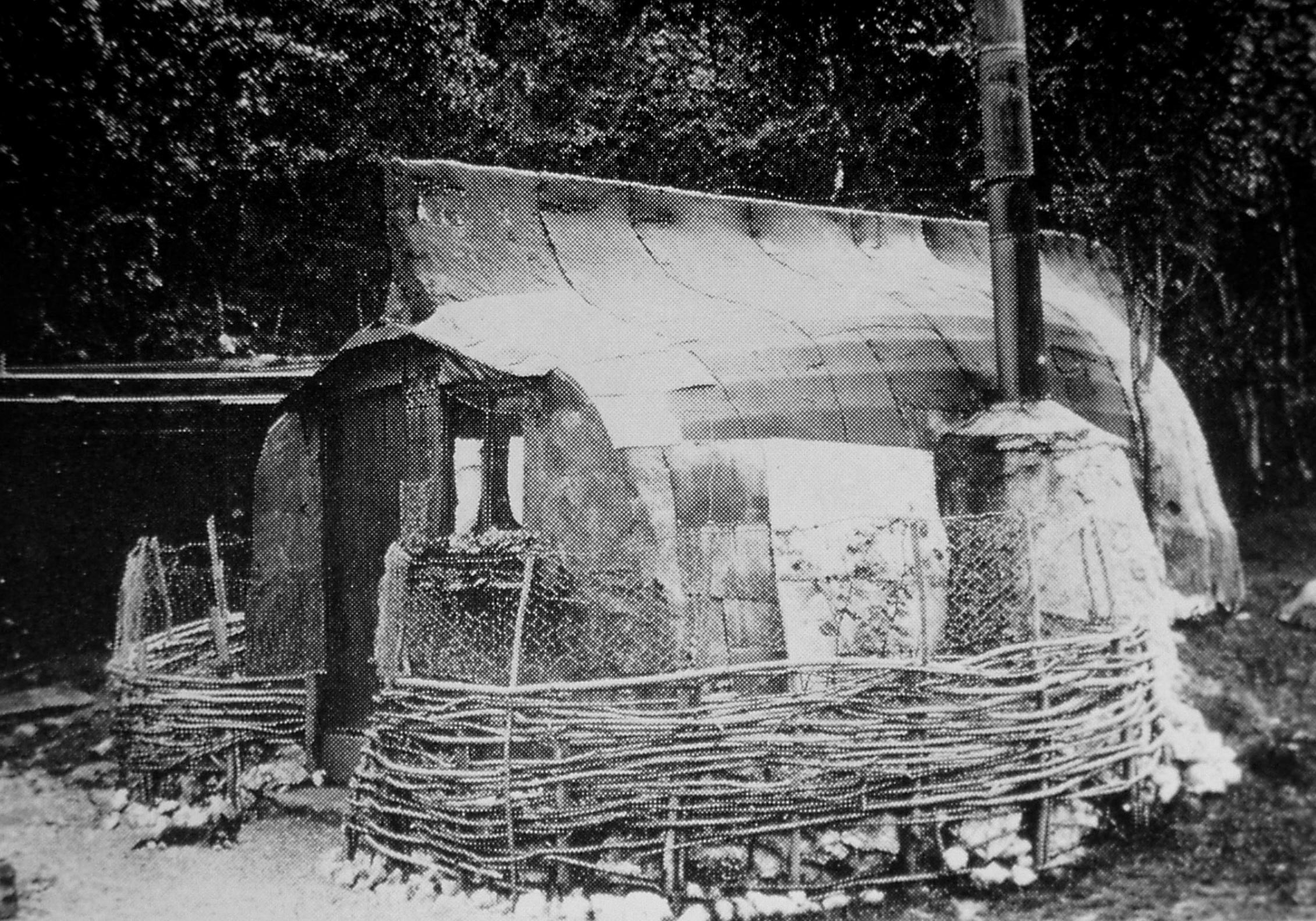

An old boat turned into a home, at Pett Level in 1910.

An old boat turned into a home, at Pett Level in 1910.

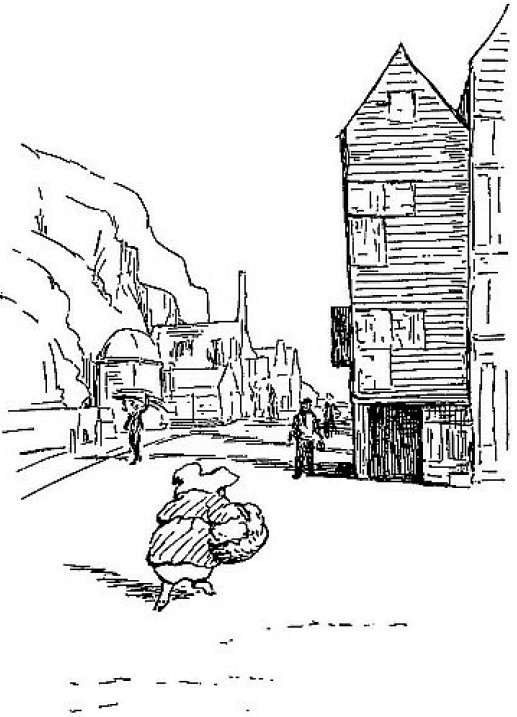

From ‘The Tales of Little Pig Robinson’, by Beatrix Potter, published 1930, set in the town of “Stymouth” (Hastings):

“There are rope walks, and washing that flaps on waggling lines above banks of stony shingle, littered with seaweed, whelk shells and dead crabs. … And there are marine stores that sell spyglasses, and sou’westers, and onions; and there are smells; and curious high sheds, shaped like sentry boxes, where they hang up herring nets to dry;

East beach Street 1865. A large trading vessel is under repair.

East beach Street 1865. A large trading vessel is under repair.